Last spring, a friend of mine asked me if I’d visit someone who had been transferred to a rehabilitation facility near me. Marianna had been in a terrible car accident that had paralyzed her and left her with all kinds of physical challenges. She was from Michigan and didn’t know anyone in town, and as a fellow poet, she longed for someone who was like-minded to be able to connect with.

I thought it was just the kind of God-thing I tried to stay tuned into, this invitation to visit a stranger. I felt pretty good about myself, actually. Look at this good deed I have the opportunity to do, to give my time and attention to this woman I don’t know. Of course I’d go!

I texted with Marianna’s sister, Kate, who lived states away to coordinate our first visit because Marianna didn’t have use of her hands to text. After we figured out some details, Kate said, “I hope any experiences you have with my sister Marianna are joy filled and wonderful for you as well. She is a very deep soul.”

I “hearted” her message, but inside, I felt a little embarrassed. Until that moment, I had only thought of our time together as me blessing her.

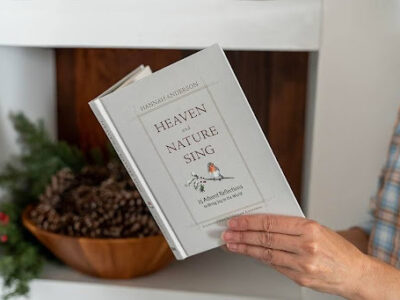

Blessed Are the Rest of Us: How Limits and Longing Make Us Whole by Micha Boyett

Image Courtesy of The Lucky Few Podcast

In the prologue to Micha Boyett’s second book, Blessed Are the Rest of Us: How Limits and Longing Make Us Whole, she asks:

“Who matters? That’s the question I’d been asking in the years since I answered a call from the genetic counselor four months into my pregnancy with Ace… I had given birth to two healthy little boys before that pregnancy. My older kids were developing as expected—strong, both in the ninety-fifth percentile in height, both good eaters and early talkers. I had no reason to think my third baby would be any different. I was thirty-five and healthy. My husband and I had hoped my twenty-week ultrasound would reveal that this time around it was a girl. It had to be—the pregnancy had felt exceptional, distinctive.”

Instead, the geneticist’s phone call confirmed that there was a 99.7 percent chance Boyett’s third child would have Down syndrome.

In the years following that diagnosis, Ace has challenged Boyett’s understanding of God and deepened and enriched her understanding of what Jesus was trying to communicate in the Beatitudes, the beautiful poem that opens Jesus’ most famous sermon, the Sermon on the Mount. Braiding together her meditations on each of the Beatitudes with moments of parenting that are both humble and real, Micha presents a soul satisfying reading of what it means to be blessed in the eyes of God.

“This is a book about that preface [ the Beatitudes ] and what it reveals to us about human value, how we find our identity, and who deserves honor,” writes Boyett. “It’s a book exploring what it means to be blessed, that overused, often trite, hashtag of a religious word no one ever really knows how to define, a word I recently found stitched into cotton pajamas on the rack in TJ Maxx, an adjective that some biblical scholars translate from the original Greek word makaroi as ‘happy,’ ‘favored,’ or even ‘flourishing.’ Blessed is the word Jesus assigned to the weak, the weary, and the worn out.”

Who matters? When vital nerves in your spinal cord are severed and you’re left paralyzed from the neck down and people say you’re lucky to be alive, do you still matter? When society says that your son’s intellectual disability renders him either a burden on society or an angel doll baby, does he still matter? If you suffer from a chronic illness and can no longer contribute to the capitalism machine, do you still matter?

In the Beatitudes, Jesus says you do, abundantly so, counter-culturally so, so much so that you don’t just matter, you will inherit the kingdom of God. You will receive mercy. You are blessed.

Kate’s words about her sister shook me out of society’s hierarchy about the givers and receivers, the useful and the useless, and reminded me of the subversive love of God’s kingdom. The first shall be last. Blessed are the humble, the meek, the poor, the ones who receive mercy, the ones who hunger for righteousness.

Boyett writes her own rendering of the poem by Jesus at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, and through each chapter of her book, she explores what Jesus’ Beatitudes mean for “the rest of us,” those of us who fall outside of who the world views as blessed. Each line of the Beatitudes is a “macarism,” a Greek term defined by Dale Bruner as “a compelling proclamation that expresses a blessing. An exhortation to live a particular way. A congratulation to specific persons in specific conditions.”

“If we embrace his vision,” Boyett writes, “his poem offers us a new script, a new way of being human. Jesus reveals the really real underneath what we think we know about God and what we think we know about the world. His poem tells us that there is a dream that belongs to the divine one, and it’s a dream about blessing. And in the dream of God, blessing is rarely what we think it is.”

I went into my relationship with Marianna thinking that I was the one who would be doing the blessing, blessing this stranger with the pleasure of my presence, when of course God had more in mind, abundantly more. For the kingdom is made of true relationships, lives given and shared in the nitty-gritty realities of pain and loneliness, anxiety and despair, fear and anger, shared and healed with compassion and love, empathy and concern, action and prayer.

The blessing of God’s love is always far grander than we could have ever imagined. Boyett lends us eyes to see the possibility of that grace-filled kingdom reality right in front of us.

You can find Blessed Are the Rest of Us: How Limits and Longing Make Us Whole on Amazon.com, in your local independent bookstore, and from other major book distributors.

Copyright

2025

Root and Vine

Copyright

2025

Root and Vine