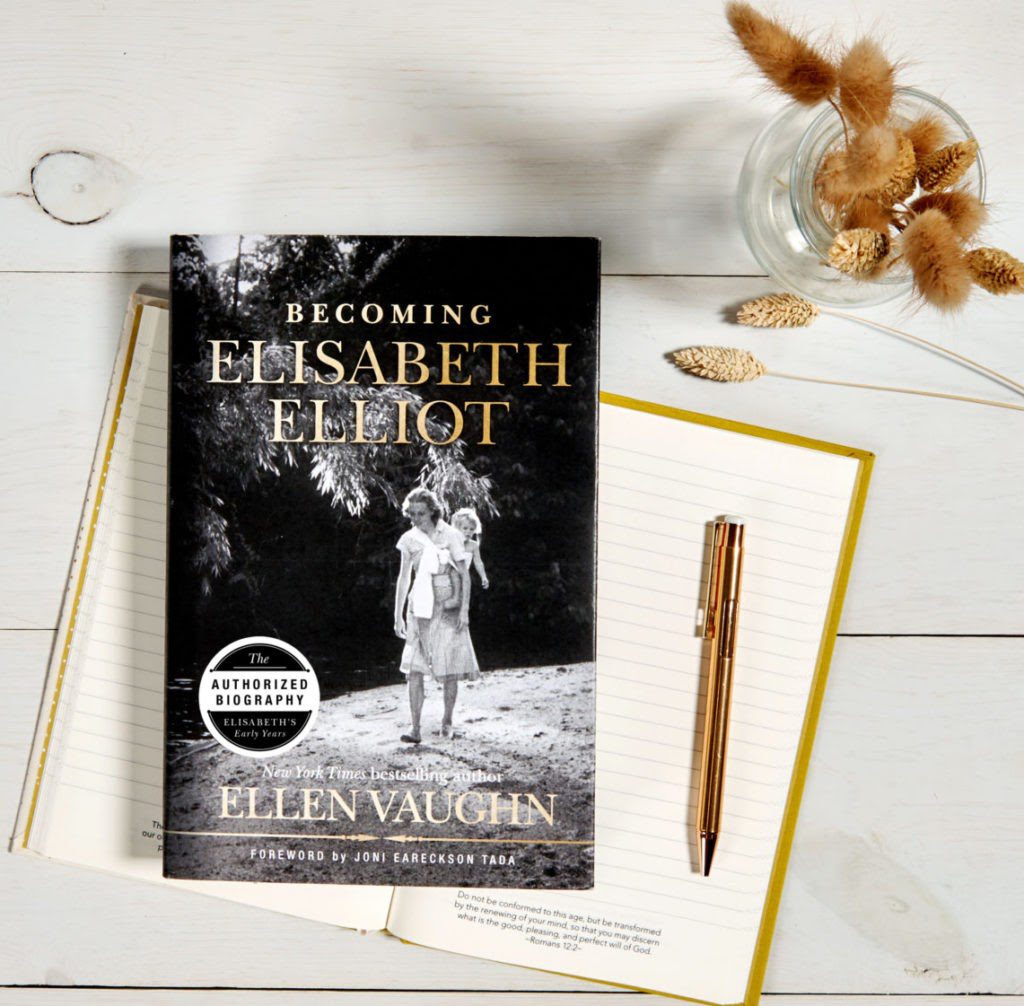

What drives a young widow to return with her toddler to the jungles of the Amazon to live with the tribe that murdered her husband just 20 months earlier? Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, part one of Elisabeth Elliot’s biography by Ellen Vaughn, looks beyond the legendary story of Jim and Betty Elliot’s mission to the Waodani tribe of Ecuador. The story looks into the heart and mind of Betty Elliot to understand how she arrived in that jungle and the road God took her down shaped her life.

In Response to the New Biography, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, by Ellen Vaughn

Not growing up in a Christian subculture, I had a vague memory of the story of Jim Elliot, the passionate missionary who along with four other men, was speared to death by an unreached Ecuadorian group in the 1950s. I knew even less of his young bride, Elisabeth Elliot, who returned to live among the Waodani, the tribe that made Jim a martyr.

With this little bit of background, I began reading Becoming Elisabeth Elliot with some relative skepticism. I mean, what crazy, possessed person takes her toddler back into the jungle to learn about and share the Gospel with the people who murdered her husband? The world and its opinions about global missions have changed since Elisabeth ventured into the Amazonian jungle. While we still admire the faithful few who venture into the mission field, some of the church, and the vast majority of the world, tends to question these life choices today.

My opinions have evolved since I slapped an “Every Tribe, Every Tongue, Every Nation” bumper sticker on the car I drove in college. There was a time when I thought of surrendering everything to the alluring sacrifice of a life of missions, but that zeal fizzled out in the first couple years of marriage. My husband and I pursued other—more comfortable—calls on our lives. Like many of our generation, the faith of our starry-eyed, save-the-world-ism encountered questions not always answered to our satisfaction. The concerns over imposing our Western culture and American ego on unsuspecting tribal people began to color our perspective on the value and intentions behind global mission work.

To put it frankly, many of the short — and long-term — mission trips we encountered came across to us as just opportunities to have an international vacation on someone else’s dime. It was a self-serving chance for young adults to experience the world for what it was beyond the walls of the capitalistic kingdom of their youth. I didn’t have the same opportunities the young Elisabeth Elliot did, meeting missionaries on leave from overseas and learning what their lives were really like.

For that reason, when I began to read Elisabeth Elliot’s story, I brought along the skepticism I’ve carried about global missions, preparing to be irritated by her story. Perhaps her biographer, Ellen Vaughn, knew this was a potential reality about her reader. From the very beginning, Vaughn reset expectations for what her biography aimed to do: “I wanted to introduce this gutsy woman of faith to a generation that does not know her. Was she perfect? By no means. Was she committed to living her life flat-out for Christ, holding nothing back? Yes. She was curious, intellectually honest, and unafraid. Not just about living with naked people who could kill her while she slept, but unafraid that the quest for Truth might lead her to an inconvenient conclusion.”

Vaughn forced me to abandon my embarrassing assumptions about Elliot within the first few pages of her introduction. She replaced the two-dimensional stereotype I expected to encounter with a frank, compelling summary of a complex and fascinating woman of faith I immediately wanted to know. I have often hungered for the companionship of women who are, as Vaughn describes, “curious, intellectually honest, and unafraid.” Vaughn made me wish I had been introduced to Elisabeth Elliot sooner.

What follows Vaughn’s introduction is a powerfully written, well-researched, and documented journey through the coming of age of Elisabeth Elliot. The biography included what formed her foundation of faith and what events of her life God used to change and shape her heart and mind. Using Elliot’s substantive body of work, personal journals and letters, and eye-witness accounts, Vaughn weaves together an intimate narrative that accommodates both cultural and historical context. We get to know Elliot within the broader world in which she dwelt.

If a question is triggered as you read, Vaughn is quick to show the other side of the coin. The painfully long courtship between Elisabeth and Jim, the strained missionary relationship between Elisabeth and Rachel Saint among the Waodani tribe, and the unbelievable faith of Elisabeth herself was shown in detail. Most of the time, Vaughn keeps herself hidden in the telling of Elisabeth’s story, but her personal interjections are a breath of fresh air for the reader. In the case of the five-year courtship, Vaughn chimes in, “It’s an understandable critique when we outsiders examine the voluminous trail of letters and journal entries that paper the path of Betty and Jim’s five-year courtship. Many of us would have gone running after the first year or so. But as Betty’s biographer, chafing at the tortured days and weeks and months of waiting for an outcome that seemed long-ripe for the plucking, fully within the smile of God, I’m reminded that it’s difficult to ascertain just how God leads any of us…. The key fact, and the great transferable truth that comes from these sometimes maddening people, is this: Betty and Jim were determined to obey God’s leading as they discerned it, whatever the cost.”

Vaughn doesn’t shy away from the question readers bring to the book regarding the spirit behind the mission work either. “Critics would later accuse the missionaries of being in collusion with American oil companies or the government, or idiots determined to impose Western culture on a pristine indigenous people. But the five men did not go to them for profit, fame, or ignorant cultural imperialism, but simply because they knew that Jesus offered the people eternal life in heaven and a new, non-violent way of living here on God’s green earth. Good news. For free.”

This message humbled my initial reaction and sat with me throughout the rest of the book. What do I really believe about the value—and the cost—of following Christ and preaching the Good News, even to the ends of the earth, or to the grave? Have I been a Christian so long I forgot the power of the Gospel in my life, the freedom I gained, and the urgency I felt to share the message of Love and forgiveness with everyone I encountered? Elliot’s complex and evolving faith challenged and encouraged my own, and Vaughn’s retelling brought insight and perspective to frame Elliot’s story within the larger questions that burden us today.

By examining how Elliot sought answers to the tragedies and conflicts in her life, Vaughn invites the reader to reflect on the present, filled with its own personal and public tragedies. With so much senseless loss, Vaughn points to Elisabeth’s enduring faith, a faith rested in the presence of a sovereign God whose transcendent power can redeem anything. Followers of Christ need this reminder, and so we are given testimonies of faith to encourage us along our journey.

I am grateful for Ellen Vaughn’s eloquent retelling of the events that shaped Elisabeth Elliot. Elliot’s story emboldened my own faith. It reminded me that the message of the Gospel is worthy of great risk. Vaughn accomplished the hard work of uncovering the many complexities of Elliot in order to bring her to life on the page. It was lovely to meet her.

Copyright

2024

Root and Vine

Copyright

2024

Root and Vine